My Name is Eugenia Sakevych-Dallas, the Film

The Holodomor was a famine-genocide of Ukrainians committed by the Soviet Union in 1932–1933, taking the lives of millions. This project uses the Holodomor as a case study to explore how storytelling can communicate trauma responsibly and meaningfully, and to open broader conversations about genocide. Dozens of survivors’ accounts were studied, with particular focus on the life of Eugenia Sakevych-Dallas, a survivor who later became a successful model in Europe and the United States. Her 1984 testimony before the U.S. Congress contributed to the Holodomor’s official recognition as genocide by the United States and several other countries.

To guide the process of communicating such a complex and painful history, the Difficult Histories Storytelling Framework was developed specifically for this project. Designed to support Western audiences encountering genocide narratives, the framework shaped the structure, tone, and interpretive approach of the film. Using this model, the short film traces the historical context and human consequences of the Holodomor while guiding viewers through Eugenia’s life story. Sparse historical and personal photographs are deconstructed and reassembled through hand-drawn elements, sound design, and AI-assisted techniques, creating a narrative that balances accuracy, emotional accessibility, and a sense of ethical responsibility.

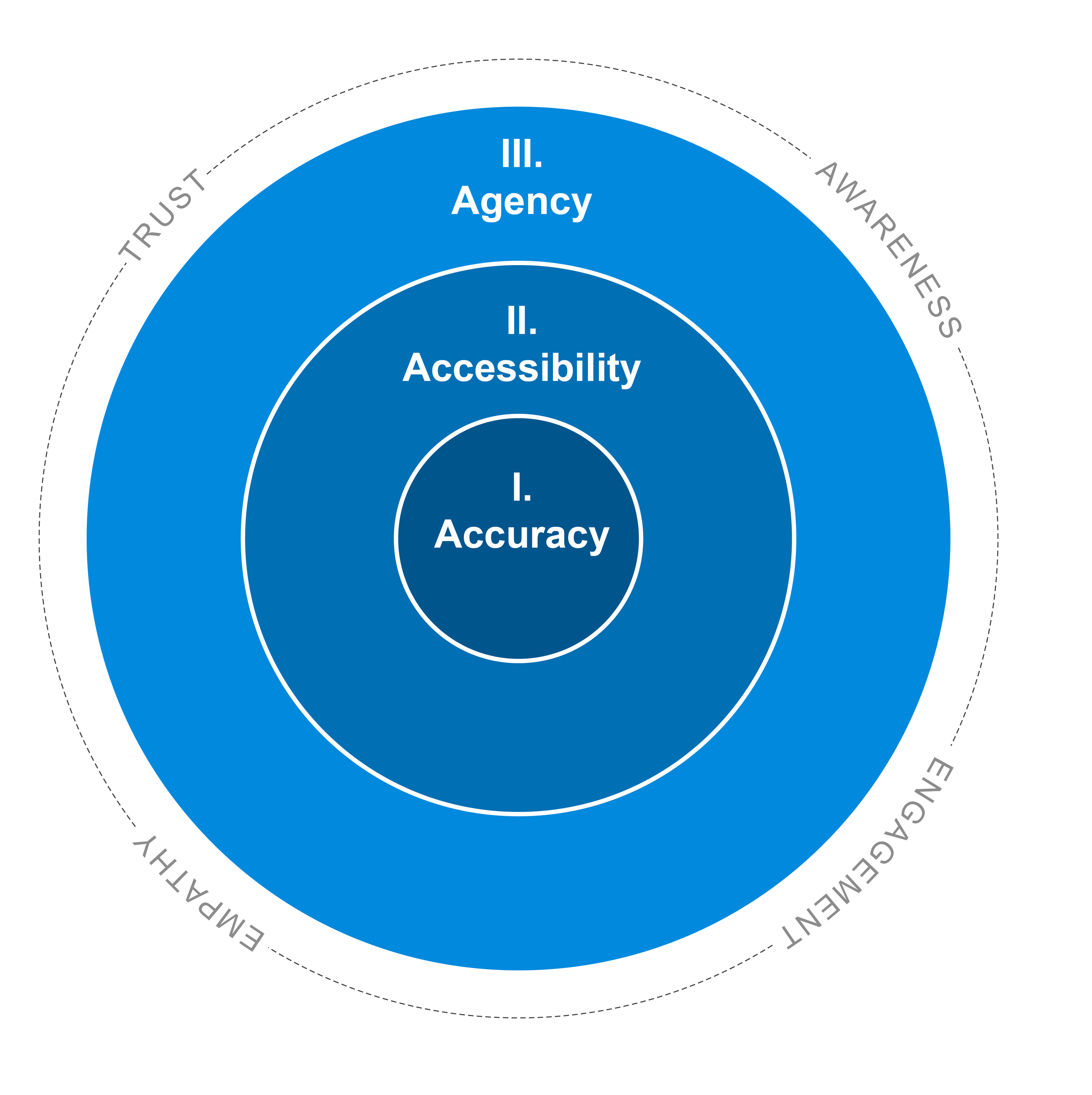

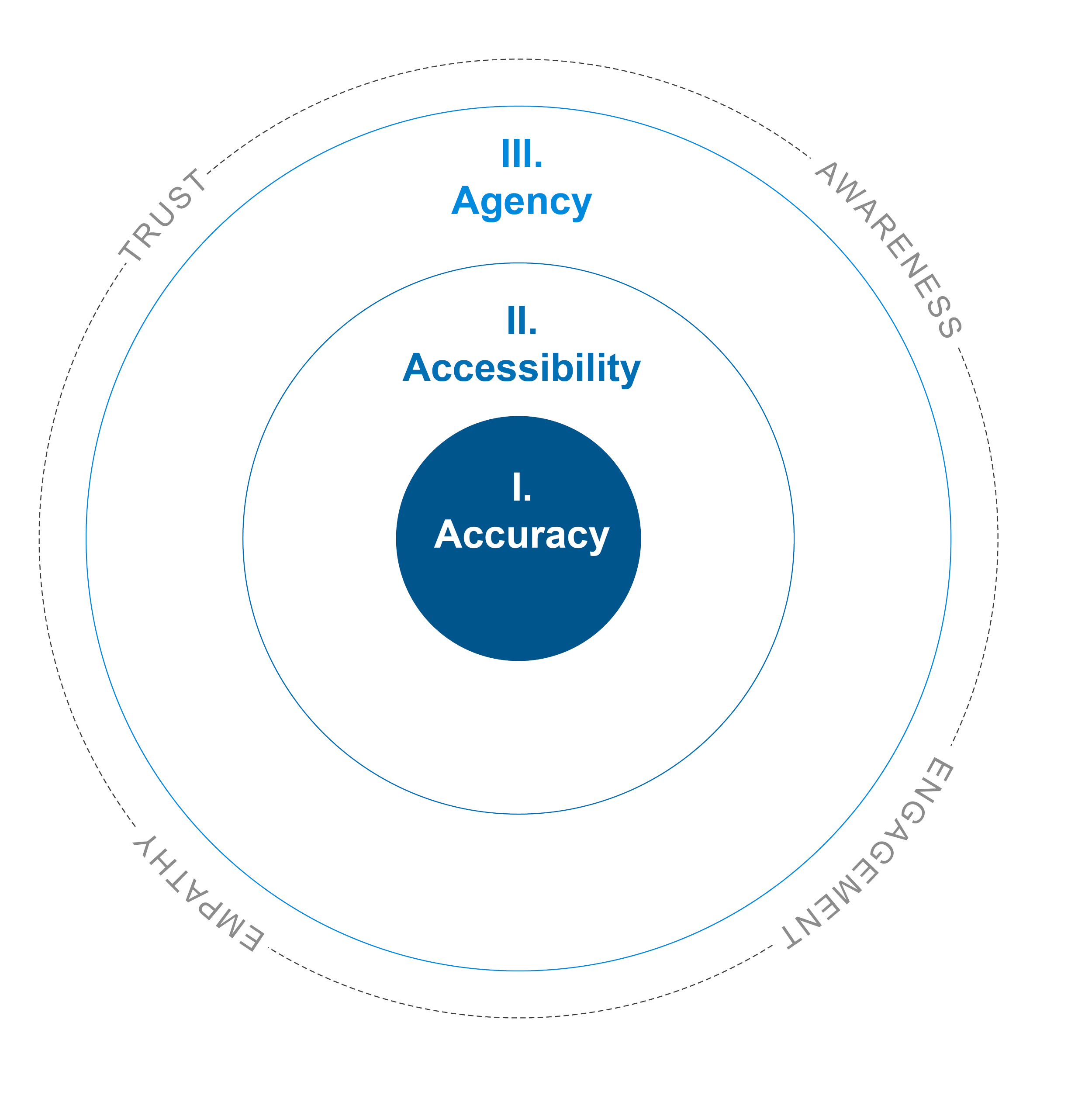

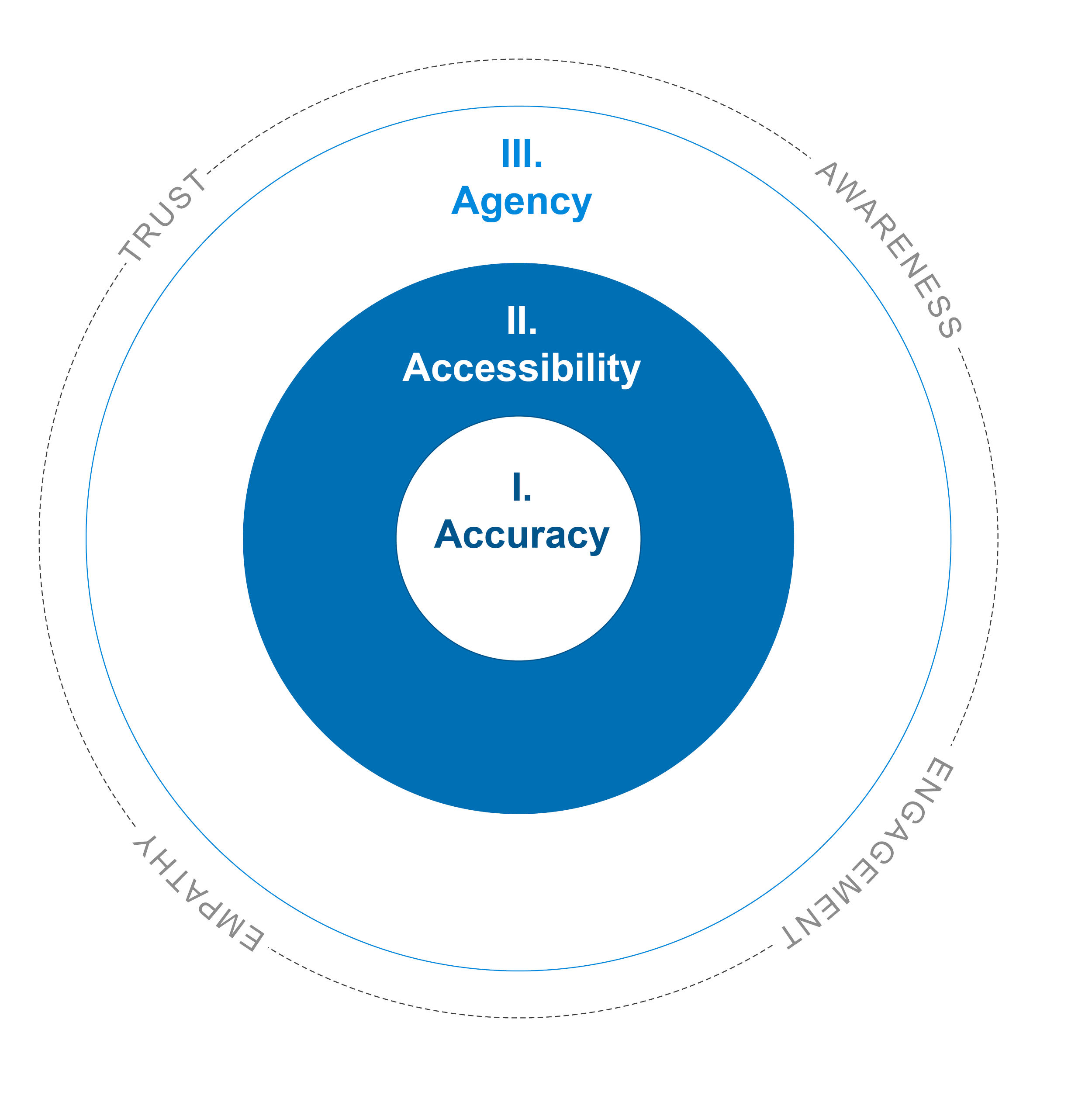

Difficult Histories Storytelling Framework

To guide my approach to representing histories marked by trauma, violence, and erasure, I work with a model I developed through my practice: the Difficult Histories Storytelling Framework. It grew out of years of research and design work focused on genocide, displacement, and memory, and it now anchors how I shape complex historical material into narratives that are ethically grounded, emotionally resonant, and socially meaningful.

At the center of the framework are interconnected principles of Accuracy, Accessibility, and Agency. These are surrounded by an outer ring of trust, awareness, engagement, and empathy, the conditions I aim to cultivate in every project. Accuracy becomes the basis for trust; accessibility nurtures awareness and empathy; and agency transforms understanding into active engagement. Together, they guide my process from truth to understanding and from understanding to responsibility, allowing remembrance to function as an ethical, living practice.

framework componentsI. Accuracy

Accuracy safeguards the integrity of truth in narratives that have often been distorted, suppressed, or deliberately obscured. It demands rigorous attention to historical evidence, contextual nuance, and the ethical implications of interpretation, ensuring that stories of trauma are grounded in verifiable reality rather than speculation or sensationalism.

II. Accessibility

Accessibility focuses on clarity and emotional legibility. Difficult histories can feel distant or overwhelming, and accessibility counteracts this by creating pathways that allow audiences to connect with the material without diminishing its complexity or weight. A trauma-informed sensibility ensures that the narrative remains respectful, humane, and approachable while maintaining historical depth.

III. Agency

Agency transforms understanding into engagement. Rather than leaving audiences in a passive state of empathy or despair, agency emphasizes resilience, continuity, and ethical responsibility. By illuminating not only devastation but also survival and human strength, it fosters a sense of connection that can motivate reflection, solidarity, and action.

I. Accuracy in the Film’s Narrative Structure

Crafting an accurate account of the Holodomor requires navigating a historical record marked by suppression and denial. Soviet authorities restricted borders, silenced witnesses, and limited access to archives, leaving significant gaps in documentation. To ground the film in truth, the narrative draws from Eugenia Sakevych-Dallas’s memoir One Woman, Five Lives, Five Countries and cross-references her account with historical scholarship and expert analysis. Her story offers a rare continuity across prewar life, famine, displacement, immigration, and activism, providing a cohesive narrative that reflects both personal testimony and historical context.

II. Accessibility Through Visual and Narrative Design

Representing genocide in a way that remains accessible without veering into sensationalism is a persistent challenge. Many viewers have no experiential reference point for such trauma, and poorly structured portrayals can risk reducing suffering to spectacle, as seen in certain commercialized depictions of genocide criticized by survivors and scholars. In this film, accessibility emerges through a balance of information, imagery, and reflective pauses. Visuals and text provide orientation; paratext offers historical grounding; silent moments allow space for emotional processing. Together, these elements support a humane and respectful experience.

II. Agency Shaped Through the Inzovu Emotional Arc

Stories of genocide often end in devastation, leaving audiences overwhelmed but unable to act. To foster agency, the film shapes Eugenia’s life around the emotional arc of the Inzovu Curve, beginning with her early childhood, descending into the trauma of collectivization and famine, and rising again as she rebuilds her life after the WW2. This structure acknowledges suffering while also foregrounding resilience, creating an arc that moves viewers from grief toward reflection, from empathy toward ethical engagement. Eugenia’s trajectory, marked by survival, reinvention, and advocacy, becomes a pathway through which audiences can connect, understand, and respond.

finding a protagonistWitnesses to the genocide: lives that hold the memory of what happened

While searching for a Holodomor survivor whose story embodied an unbreakable spirit and strength, I went through hundreds of testimonies. I found several dozen who, after enduring unimaginable hardships, managed to gain recognition in Ukraine and abroad. This list, among others, includes Vasyl Barka (1908-2003), who wrote Zhovtyi Kniaz (eng. The Yellow Prince), the first novel about the Holodomor; Kateryna Bilokur (1900-1961), a widely exhibited artist admired by Pablo Picasso; Evgeniia Miroshnychenko (1931-2009), an internationally renowned opera singer; Levko Lukianenko (1928-2018), a political dissident, Nonna Auska (1923-2013), a doctor, and Eugenia Sakevych-Dallas (1925-2014), a widely recognized fashion model.

Vasyl Barka and Eugenia Sakevych-Dallas stood out because they testified before the U.S. Congress investigation of the Holodomor in 1984. Eugenia and Vasyl spoke publicly in the face of intimidation and death threats by the Soviets. Their testimonies contributed to the U.S. officially recognizing the Holodomor as a genocide of Ukrainians.

creative conceptReanimating Tradition:

The Photo Album as Narrative Device

I was greatly inspired by the traditional way of storytelling, and I wanted to incorporate this traditional way of storytelling into a digital realm. Eugenia's story is narrated by a storyteller who presents the old photo album to the audience and brings Eugenia’s story to life with visuals. As the narrator speaks, the photos in the album come to life through colour and motion. The transition between each chapter of Eugenia's story is visually communicated through different photos in the album. This technique not only places the audience in the environment (e.g. clearly explains where they are in the story), but also contextualizes the story within a historical setting. It also allows for a smooth transition between different chapters (e.g. the transitions will not feel abrupt to the audience), and opens up an opportunity to include historical photographs of the Holodomor in the story.

Visual languageGuiding the Audience Through Visual Reconstruction to Tell Eugenia's Story

I developed a visual language by deconstructing historical and personal photographs to reconstruct Eugenia’s story visually. Hand-drawn elements were integrated to complement the aesthetics of the historical photographs, adding a personal touch while depicting the events of the Holodomor. The film’s color palette primarily features shades and tints of dark brown, off-white, and green. Color saturation varies with the emotional tone of each chapter or scene: bright and highly saturated green introduces the story, gradually fading as the narrative delves into the horrors of the famine. Scenes of hope reintroduce bright and saturated colors, aligning with the emotional shifts in the narrative.

The historical facts are presented in the form of paratext—essentially white text on a black screen. This paratext appears unexpectedly within the story, disrupting the plot and forcing it to unfold in a different direction. These paratexts represent the vicious decisions of the Soviet government, such as collectivization, class warfare, or the Law of Three Spikelets, which caught genocide victims off guard, depriving them of control over their future.

National Museum of Holodomor-Genocide, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023

University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022

Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024

Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, IN, United States, 2021